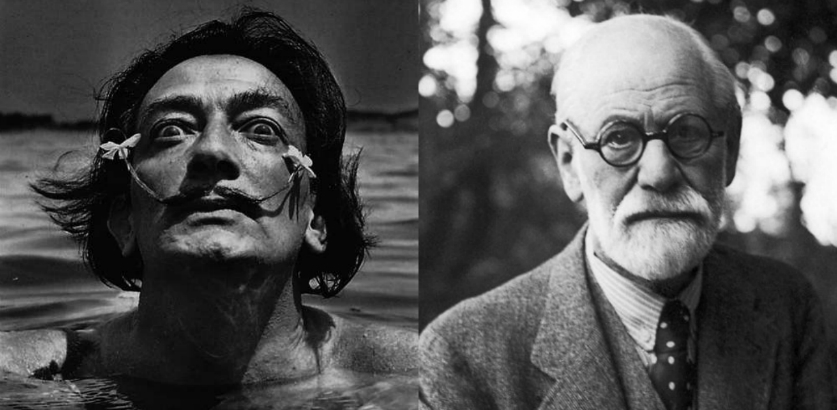

Dalí and Surrealism

Under the influence of Freud

The obsessions, torments and hidden desires hidden in the human psyche have been one of the most powerful creative engines in our history. In this respect, the year 1900 became a key date, when a real fervor to explore, interpret and understand the hidden mechanism of our mind was unleashed. It was then that Sigmund Freud published what has been one of the most controversial and relevant works in the history, not only of psychology, but also of contemporary Western thought: The Interpretation of Dreams.

Sigmund Freud: The Muse of the Surrealist Group

With the introduction of such revolutionary concepts as the unconscious, Freud challenged the traditional view of humans as rational beings, whose true nature would be dominated by erotic and aggressive drives that, having been repressed, manifested themselves in the form of dreams.

His revolutionary ideas, as has so often happened throughout history, caused phobias, but also great philias. Among the circle of intellectuals who were astonished by the new Freudian postulates, it was the members of the surrealist movement who welcomed it with the greatest enthusiasm.

In fact, it was André Breton who, as the founding father of the movement, appreciated and highlighted Freud’s findings in the field of the unconscious and dreams. As we can deduce from the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), the vindication of the dream as one of the fundamental ways of liberation of the psyche became one of the banners of the movement and, consequently, Freud became one of its main referents.

The psychoanalytic doctrine inspired not only the surrealist theories, but also put them into practice, through new techniques, such as frottage or decalcomania, which facilitated the loss of control and the reencounter with a primary vital nature that finds its most genuine expression in the unconscious.

The psychoanalytic doctrine inspired not only the surrealist theories, but also put them into practice, through new techniques, such as frottage or decalcomania, which facilitated the loss of control and the reencounter with a primary vital nature that finds its most genuine expression in the unconscious.

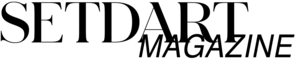

Dalí and his obsession with psychoanalysis

Dalí’s work is intimately linked to the most innovative discoveries of the time. Atomic energy, the DNA helix, the theory of relativity and, of course, psychoanalysis, became the germ that unleashed the creative torrent of the Empordà genius.

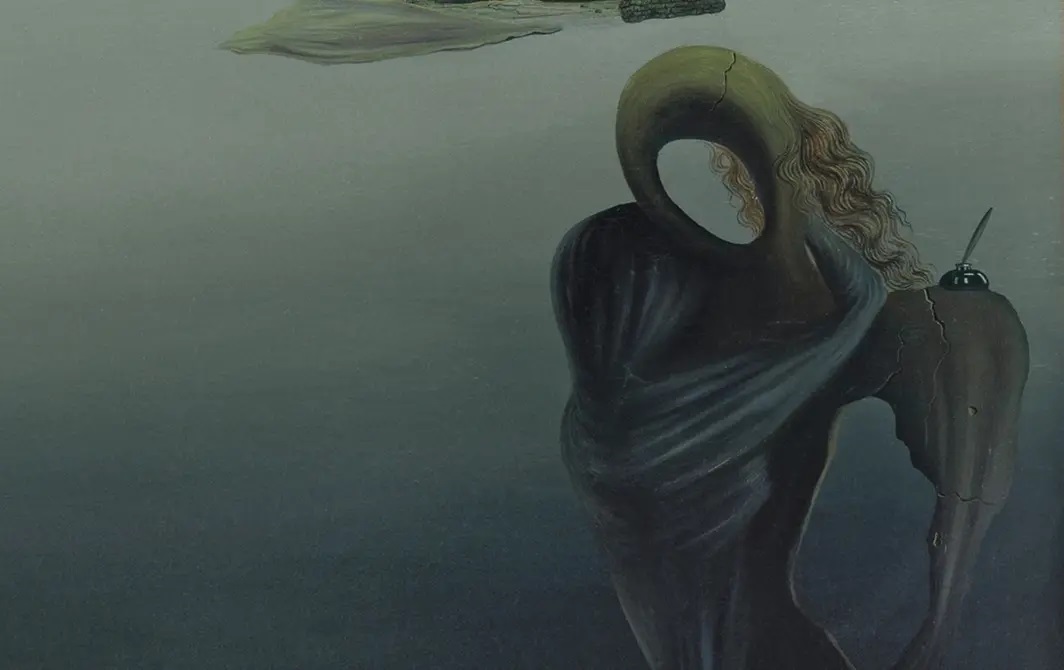

Sigmund Freud’s discoveries about the unconscious and dreams were like an open window through which Dalí found a space where he could transfer the human psyche and externalize his memories, obsessions and hidden desires.

In fact, the inordinate interest in the theories that he extracted from reading The Interpretation of Dreams, resulted in several attempts to meet his admired Freud, which did not materialize until 1938, thanks to the efforts of the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig and the poet Edward James. At that meeting, held on July 19, 1938, Dalí tried unsuccessfully to get Freud to endorse his paranoiac-critical method, in which he argued that it was possible to create images that do not exist in reality, but that presented it transformed and enriched with symbolic elements and deformations, which he found similar to those of dream work.

There is no doubt about the influence that Freudian theories had on Dalí, and we can find in all his work the imprint of some of the most important theories of the Viennese psychiatrist. Proof of this is the motif of the melted clock that, on so many occasions, starred in Dalí’s work, becoming one of the most representative and praised surrealist objects of his career. As a great reader of Freud, Dalí supported the Freudian concept of the “elasticity of psychic time” (that of memory and dreams) by giving it a unique visual form. It should also be noted that Dalí’s works, starring melting clocks, contain an underlying critique of the rigidity of time in modern society, where people are often dominated by the clock and the concept of linear time.

Despite the misunderstandings, misunderstandings, and struggles of egos that Freud and the surrealists sometimes had, the admiration they felt for him prevailed above all else, thanks to the dream they shared of liberating human beings from the slavery imposed by the dictates of reason.