At the beginning of the 20th century, when European art was struggling between the legacy of Impressionism and the urgency for new forms of expression, a group of French artists emerged, ready to break with all conventions. They were called fauves – “wild beasts”- for their wild use of color and their contempt for academic canons. Although the movement was short-lived, its echo resonated beyond France, transforming the European art scene. In this context, a name that deserves to be rediscovered stands out: Francisco Iturrino, an artist who introduced in Spain a radical colorist vision in tune with French Fauvism.

What was Fauvism?

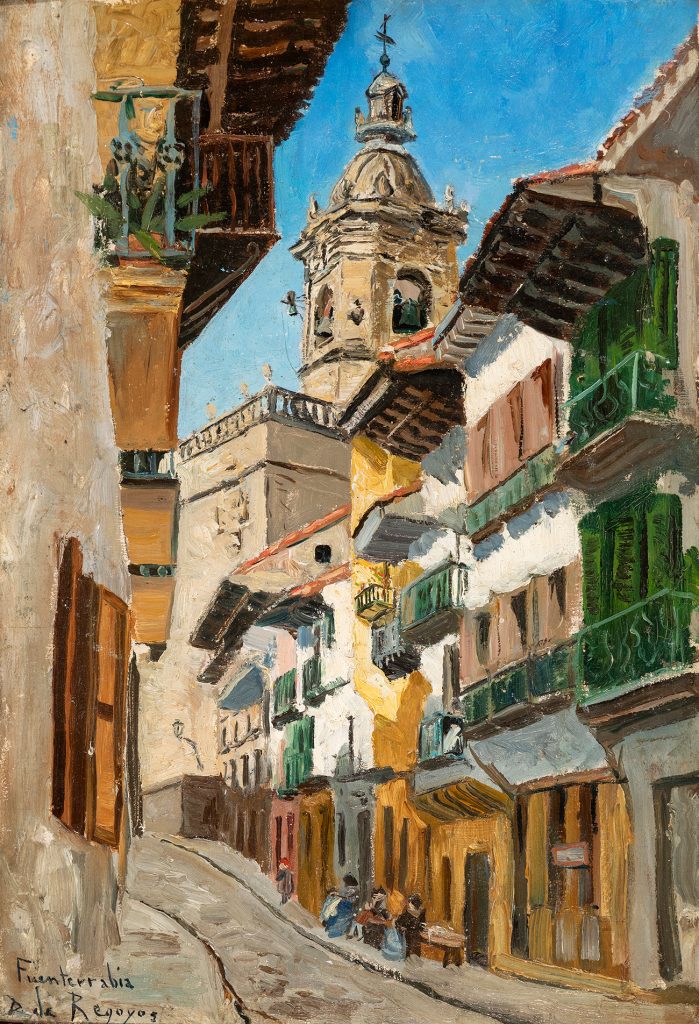

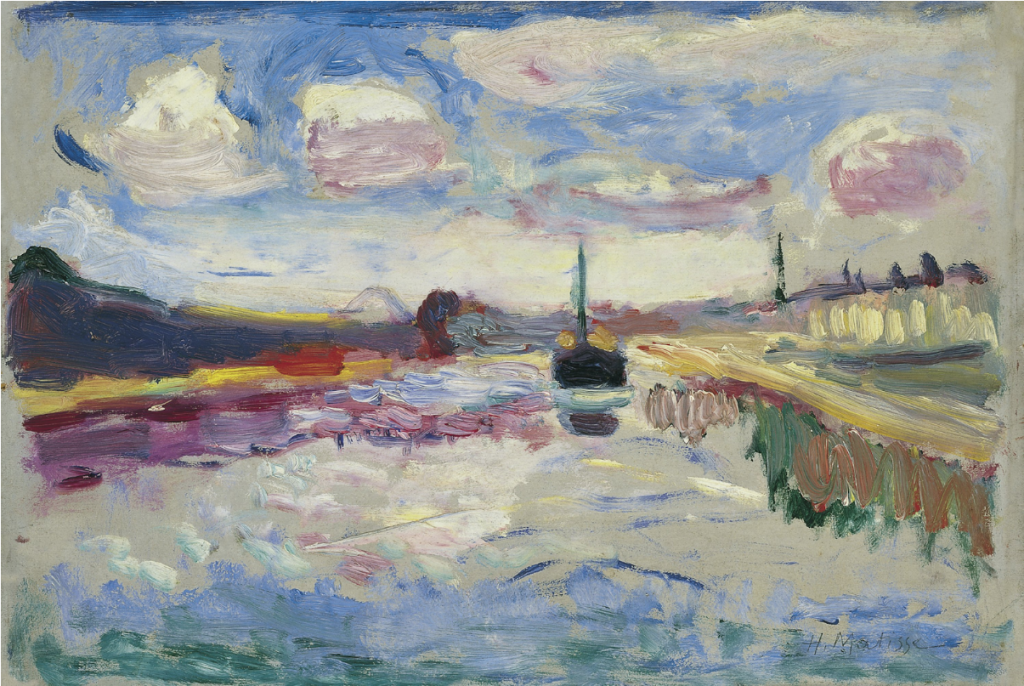

Fauvism was officially born in 1905, when an exhibition at the Paris Salon d’Automne baffled critics. In a room shared by classical sculptures and vibrantly colored paintings, critic Louis Vauxcelles coined the phrase “Donatello among the wild beasts” to describe the contrast. From this emerged the term “fauves,” proudly adopted by the artists themselves, including Matisse, Derain and Vlaminck.

Behind the apparent chromatic chaos, the Fauves pursued a clear idea: to free color from its merely descriptive function to turn it into an emotional protagonist. A beach could be purple, a face green, and a landscape a symphony of reds. The idea was not to copy reality, but to express an intense, direct and vital emotion.

Francisco Iturrino: the most Fauvist Spaniard (without being entirely Fauvist)

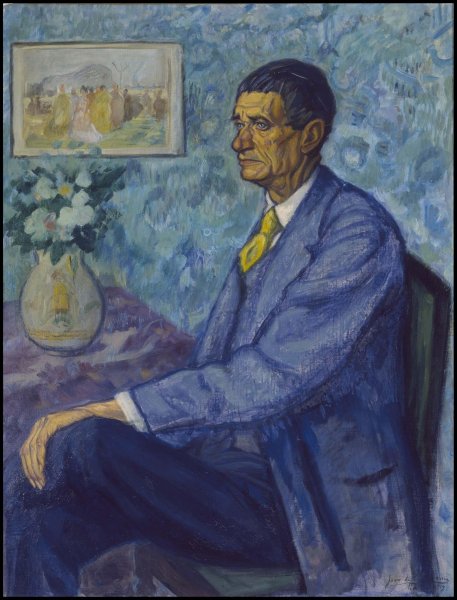

Francisco Iturrino, born in Santander and raised in the Basque Country, developed an artistic career that transcends any geography. This Cantabrian painter, a tireless traveler, was part of the most vibrant circles of the European avant-garde and was one of the few Spaniards who exhibited alongside Matisse at the 1905 Salon d’Automne.

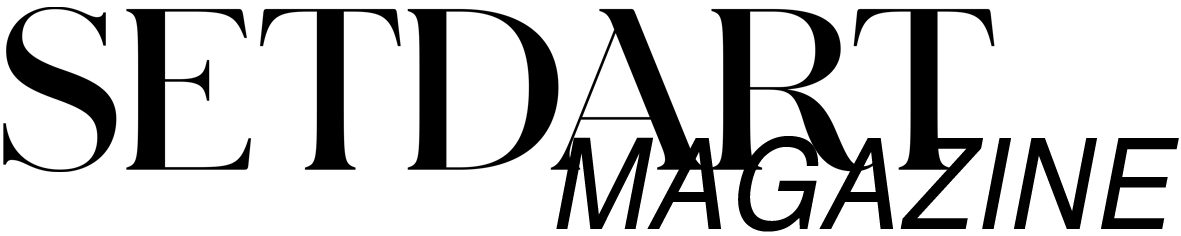

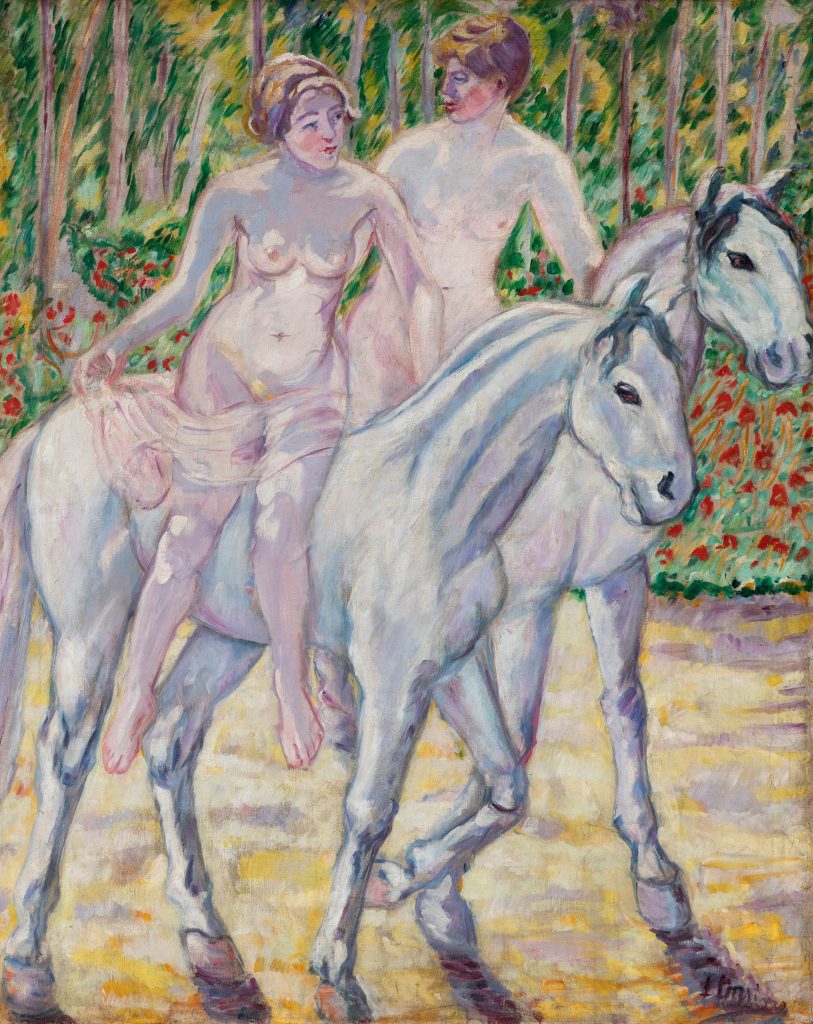

Although he was not an orthodox Fauvist, the Cantabrian painter absorbed the energy of the movement like few others. His palette exploded in oranges, violets, greens and yellows; his brushwork became loose, sensual, festive; and his subjects – female nudes, Andalusian gardens, popular festivals – celebrated life with an intensity unusual in Spanish art at the time.

A paradigmatic example is Young people on horseback, a work that is related to others such as Nudes in a Landscape, from the Reina Sofía Museum collection. In these paintings, Francisco Iturrino does not seek realism, but the exaltation of a state of vitalistic grace.

Matisse in Spain: a decisive journey

In 1910, Matisse traveled to Spain at the invitation of the Cantabrian painter. Together they explored Seville and other Andalusian cities. The imprint of the south would be decisive in the evolution of the French painter. This connection reveals Iturrino’ s historical relevance as a mediator between the French avant-garde and the Mediterranean spirit.

Echoes of Fauvism in Spain

Fauvism in Spain did not form a school as in France, but its influence was felt in several contemporary artists. Among them:

- Joaquín Sunyer, although he later adopted a more sober and classicist style, experimented with vibrant color and modern compositions in his early days.

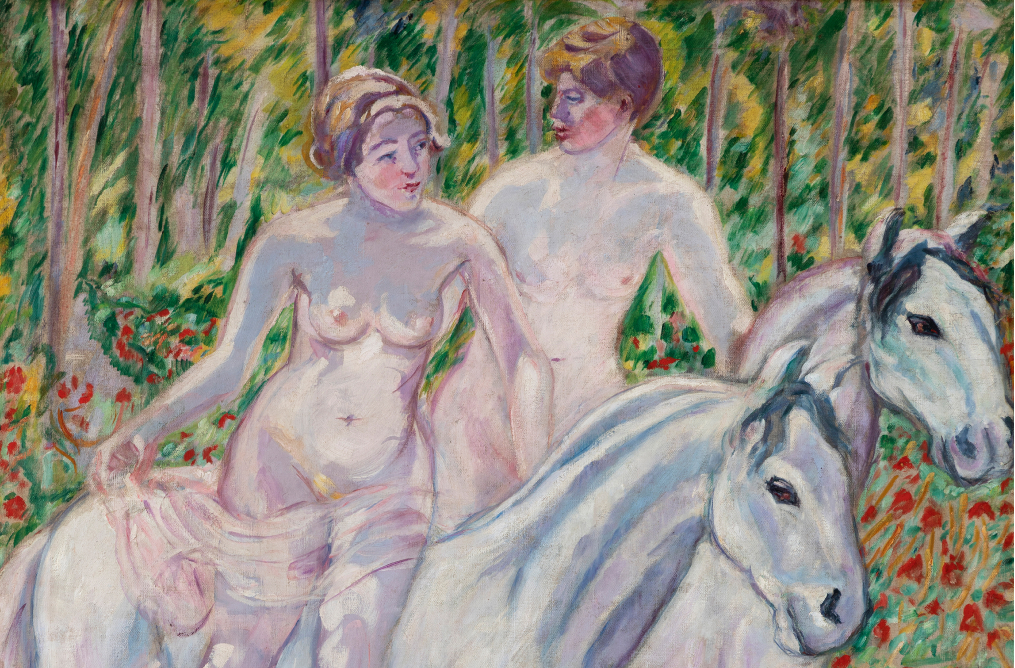

- Darío de Regoyos, close to impressionism, showed moments of chromatic audacity that approached the Fauvist universe.

- José Gutiérrez Solana, with his somber and expressionist vision, shared with the Fauves a subjective and intense attitude towards the world.

- Even Picasso, in his early stages, briefly flirted with a coloristic and decorative aesthetic before diving into Cubism.

The legacy of Fauvism

Although Fauvism lasted barely three years (1905-1908), its legacy was profoundly influential. It paved the way for German Expressionism, with its subjective exaltation of color and formal distortion, and directly influenced the emergence of Cubism by freeing painting from its dependence on mimesis. As Pierre Courthion pointed out:

“Without the chromatic liberation of Fauvism, Cubism would have been unthinkable.”

In the Spanish sphere, Fauvism did not generate a formal school, but its influence was lasting. It seeped into the margins of the academic system and among artists connected to European movements. It was not an explicit adherence, but a resonance that helped consolidate the path towards modernity.

Francisco Iturrino, hinge between two worlds

In this context, Francisco Iturrino represents much more than a sympathizer of color. His work is a historical hinge, a turning point between two realities: on the one hand, the Spanish fin-de-siècle world, anchored in symbolism and costumbrismo; on the other, the promise of a free, subjective and sensorial painting.

His work anticipates routes that would later be taken by artists such as Joaquín Torres-García, in his post-noucentista period, or even Joan Miró, in his transition from poetic realism to symbolic abstraction.

Moreover, Iturrino’s work is deeply nourished by Spanish identity without falling into the folkloric. His exaltation of the south, of the Andalusian light, of the feminine body and of ornamentation connects with a vital and decorative Hispanic vision, in dialogue with Islamic art and popular baroque.

In this sense, his legacy is not only aesthetic, but also cultural. He demonstrates that the modern does not have to be alien to the local. On the contrary: the Cantabrian painter achieves a personal synthesis between European avant-garde and Mediterranean identity.

Rediscovering Francisco Iturrino today

In short, Fauvism in Spain was not a fashion, but a spark that ignited deeper processes. And at the heart of that transition is Francisco Iturrino: neither completely fierce nor completely classical, but absolutely modern. To rediscover his work is to understand that modernity was also lived -and transformed- in the Iberian Peninsula.

Discover the work of Iturrino and other artists linked to Fauvism in Setdart’s upcoming 19th and 20th Century Classics auction.