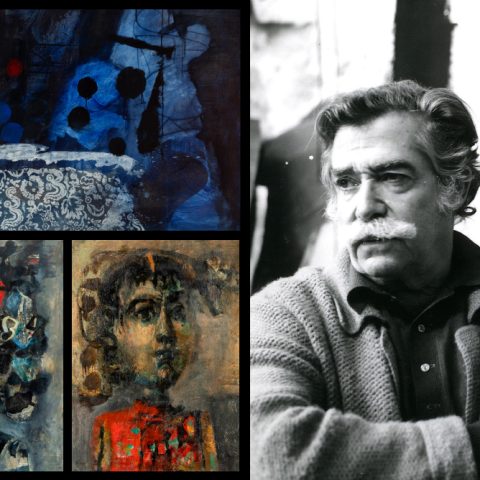

Faced with the works of Manolo Valdés we cannot help but wonder what Velázquez, Matisse or Picasso would think when they saw their transfigured masterpieces. Be that as it may, what is absolutely certain is the resounding international success that the Valencian artist has achieved thanks to a particular revision of the history of art that makes us question the reality of the times and of artistic practice itself.

From his beginnings in the 1960s to the present, Valdés’ work has evolved with absolute coherence, exploring and conquering new artistic territories from a deep knowledge of the history of art and the deepest admiration for his great masters. However, far from contemplating them from afar, Valdés rescues and takes from them those aspects of his art that he considers more appropriate to carry out a an apotheosis exercise of reinterpretation and recontextualization of the very history of art with which, decade after decade, he has forged his unmistakable creative universe.

Far from falling into the monotony that could be produced by the reiteration of the same formula, Valdés reveals his immense ability to structure his work under the same common denominator, evolving and reinventing it in each of its facets. This reformulation is evident in the pair of works under bidding, whose distance is not only due to the 20 years of difference that separate them, but also to an aesthetic discourse that, despite starting from the same approach, differs radically from each other.

In fact, after finishing his time as a member of Equipo Crónica, Valdés began in the 80s a period of maturity and creative growth, which led him definitively towards that personal and genuine style to which he has remained faithful ever since.

In sculptures such as “Reina Mariana en art deco”, the three-dimensional experimentations that the artist carried out at the beginning of his solo career materialize through the iconographic theme of Velázquez’s Marian queens. Hidden under the angular volumetry of the sculpture, we guess a Queen Mariana whose Velazquez appearance has been versioned in the hands of Valdés under the primary, synthetic and geometric forms typical of art deco. However, the imperfections in the wood that it deliberately leaves exposed, take it away from the pretensions of the decorative arts to evoke a much purer and more authentic stage: that of our childhood and its playful spirit.

Along with Velázquez, Matisse was another of the great protagonists of the transfiguration and reinterpretation with which Valdés gave a second life to some of the most iconic works of our history. The fish tank that stars in our monumental work clearly alludes to the work of Henry Matisse and more specifically to “Red Fish”, of which the French master created up to twelve versions where he recreated the same iconographic motif. This starting point serves Valdés as a pretext to give light to a composition dominated by the material aspects, latent already from the choice of burlap as the support of the work. The roughness of the material, together with the prominence of the stain, the destabilization of the form and the corporeality of the pigments in very impastoed brushstrokes, make the piece an exercise that, bordering on three-dimensionality, refers us to informalist plastic art.

In both cases, the game of stylistic permutations and references to history give way to a new image that, in its complete originality and contemporaneity, manages to establish a dialogue between the art of the past and the present. In other words, it is Valdés responding to Velázquez and Matisse.

Far from limiting himself to evoking those works that are already icons of our history, Valdés takes a much more definitive and forceful step: he dissects and reconstructs themdissects and reconstructs. A perspective that, with the passage of time, will also become an enigma that future glances will decipher and update.