When we mention a genius like Michelangelo, our mind immediately travels to his masterpieces: “The Pietà”, the “Moses” or the imposing “David”. These colossal and eternal marble sculptures have transcended time, captivating for centuries all those who stop to contemplate them. The power of attraction they exert is difficult to explain, as the feelings they arouse vary according to the viewer. Beyond the success of his work, the transformative impact Michelangelo had on art is evident in his influence on other artists and on culture itself. In fact, it would be impossible to understand the history of art to this day without the seminal figure of Michelangelo Buonarroti.

The large dimensions of the sculptures mentioned above force the viewer to maintain a certain distance to appreciate them in their entirety, which generates a sense of respect and dignity. Towards the end of his life, according to Vasari, Michelangelo dedicated himself to working on the figure of Christ crucified in a smaller format. Examples of these works are the unfinished Christ preserved in the Casa Buonarroti and a sketch on paper, painted on the back of a sonnet, which is in the Vatican Apostolic Library. This model of Christ, sculpted by the master in his last years, is known in various ways, mainly through the serial works produced by bronze artists and silversmiths. The first versions, dated between 1540 and 1560, came from the workshops of Guglielmo della Porta and Sebastiano Torrigiani, who, through their bronze Christs, disseminated an innovative model of the figure of the crucified Christ.

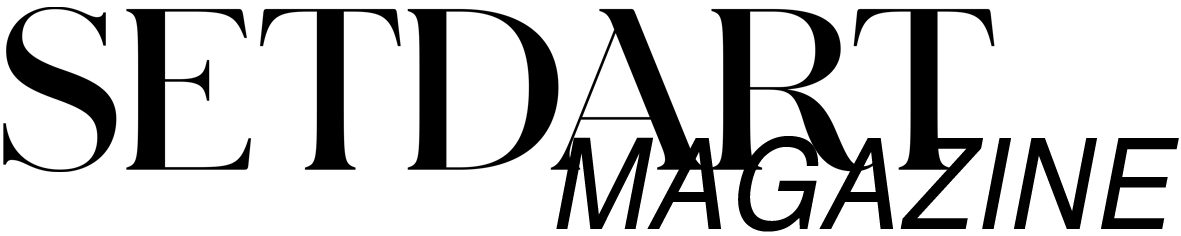

Naked Christ with perizonium removed.

Catholic tradition has represented Christ on the cross using three nails: two in the hands and one in the feet. His body is shown modestly covered with a purity cloth, known as perizonium, a device created to avoid a representation that could be sexualized. However, the Holy Scriptures relate that Jesus was stripped of his clothes to submit him to the torment of the cross. Moreover, the arrangement of the nails and the posture of the feet were consolidated as aesthetic and doctrinal elements since the 13th century. A century later, the visions of Saint Bridget introduced the idea that Christ was crucified with four nails, and with his legs crossed, a theory that, supported by recent research, indicates that this posture facilitated the asphyxiation of the condemned, preventing them from hanging from the cross. Michelangelo took all these aspects into account when conceiving his representation of Christ, integrating human realism with divine dignity. Thus, he created a nude figure, which united classical beauty with the solemnity and spiritual force of Christian sacrifice.

Christ’s face reflects the *pathos* characteristic of classical sculpture, conveying a profound expression of suffering. The tension in his body is subtly revealed through the taut veins and smoothly delineated musculature. The representation of the Savior’s naked body, because of its realism and rawness, may have been deeply provocative, which explains its scarce diffusion. To mitigate this controversy, a purity cloth was devised that could be attached to the figure without being an integral part of it, thus creating a removable vestment. In this way, the work could be contemplated both in its original conception, neat and naked, and in its censored version, covered.

“The Venerable Mother Jerónima de la Fuente” by Diego de Velázquez and “Christ” on auction at Setdart. It can be seen in the painting as Velázquez represents a polychrome Michelangelesque Christ like those of his father-in-law Francisco Pacheco.

The format of these sculptures suggests that they were intended for private devotion, away from the large chapels of the churches. These pieces were found in the bedrooms of rich patrons or in the cells of priors and abbesses. The bronze Christ, probably attached to a detachable wooden cross, could be held in the hand, facilitating its detailed observation from all possible angles. This complete view highlights the fineness with which it was sculpted, allowing us to appreciate, at very close range, details such as the closed eyelids, the curls of the hair or the wrinkles in the palms of the hands. The mastery of the work can only be fully understood through such close observation. A clear example of Michelangelo’s use of these Christs and their purpose can be seen in Diego Velázquez’s painting, *The Venerable Mother Jerónima de la Fuente* (1620), preserved in the Prado Museum. In this painting, the abbess directs a penetrating gaze at the viewer, as if she had been caught in full prayer in the privacy of her cell.

Christ in silver by Juan Bautista Franconio preserved in the museum of the Gómez-Moreno Foundation in Granada and the bronze model by Michelangelo on auction at Setdart.

Michelangelo’s model acquired a notable presence thanks to the silversmith Juan Bautista Franconio, who brought from Rome a Christ that was replicated upon his arrival in Seville around 1590. Several of these Christs can be found in different places, such as the cathedrals of Cuenca, Seville and Granada, the Royal Palace of Madrid, the Gómez Moreno Foundation and the Ducal Palace of Gandía, the latter polychromed by Francisco Pacheco. Although the model presented by Setdart clearly coincides with these versions, it stands out for its larger size. While Franconio’s silver Christs measure twenty-two centimeters, the one that Setdart bids reaches twenty-six, which underlines its singularity and relevance in the context of these works.

This difference in size may give rise to three hypotheses. The first suggests that it is a work by Franconio, who may have used a different casting to fulfill a specific commission. The second option considers the possibility that it was made by an Italian workshop, similar to those of Torrigani and della Porta. Finally, the third hypothesis, equally plausible, is that it is a replica produced by an exceptional Spanish silversmith or sculptor, such as Andrés de Campos Guevara, Juan Álvarez or Lesmes Fernández del Moral. Each of these theories opens up an interesting range of possibilities about the provenance and context of the work.

The uncertainty surrounding its authorship increases the attractiveness of this work, since its possible Spanish or Italian origin, as well as its still imprecise dating-which could be around 1540 in Italy or around 1600 in the Spanish case-and its unknown provenance make it a completely unpublished piece. Moreover, the use of gilded bronze, complemented by the silver purity cloth, is especially noteworthy, given that most similar works are of silver, gilded silver, polychrome silver or gilded copper. However, one thing is undeniable: its outstanding quality. The degree of detail, the fineness of the bronze and the perfect modeling preserve Michelangelo’s original conception. The fascination with these Christs and the genius of the master are evident in the legacy of Golden Age artists such as Francisco Pacheco, Martínez Montañés and Velázquez, who continued to explore and reinterpret their influence in their own works.