Color is a universal and, at the same time, deeply personal experience. It moves us, commands us, guides us. In art, it becomes a wordless language that communicates that which escapes form. From the mineral pigments of prehistoric caves to today’s digital screens, color has been much more than a decorative element: it is a means of thought and emotion, a symbolic tool that reflects how each culture understands the world.

Throughout history, each era has given color its own meaning. In the Renaissance, blue was a symbol of divinity and prestige, reserved for the Virgin and the wealthiest patrons, while in Romanticism, dark and contrasting tones expressed the sublime, the uncontrollable in nature. With the arrival of modernity, artists began to liberate color from its form and descriptive function. Kandinsky conceived it as a gateway to the spiritual, Matisse understood it as pure visual joy, and Rothko transformed it into expanded emotion.

The birth of Klein Blue

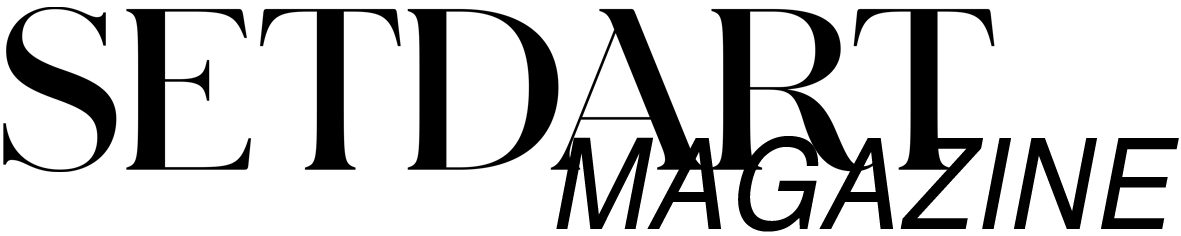

It was then that Yves Klein went a step further. With his Klein Blue, color ceased to be representation and became presence. In 1957, the French artist presented the world with a blue that would change the history of art. More than an aesthetic discovery, it was a visual manifesto: Klein did not seek to reproduce reality, but to capture the invisible – emptiness, energy, the immaterial. His blue did not evoke anything tangible; it was the absolute, the spiritual, the infinite.

International Klein Blue (IKB) was born from a collaboration between Klein and chemist Edouard Adam. Together they developed a formula that combined ultramarine pigment with a synthetic resin capable of retaining its velvety texture and luminous intensity. Thanks to this technical discovery, the blue remained vibrant, suspended on a surface that seemed to defy gravity. For Klein, this blue did not represent the sky or the sea: it was infinity itself made visible, a language to speak of the intangible, of that which transcends matter. “Blue has no dimensions,” he wrote; “it is beyond all that can be measured.”

Yves Klein and the presence of color

But the painter Yves Klein was not satisfied with just inventing a color: he wanted to make it live. Klein took Klein Blue beyond the canvas, expanding it to bodies, objects and spaces. In his famous Anthropometries, models, impregnated with his blue, stamped their bodies on large canvases while an orchestra played a piece composed of silence and breathing. In these works, the human body became a paintbrush and color, a trace of the immaterial. He also covered sculptures, sponges and walls, exploring how blue could absorb light and transform space.

Color ceased to be a visual tool and became a sensory, physical and spiritual experience. Klein sought to provoke in the viewer a sense of immersion, an instant of pure contemplation. His blue was not only seen: it was felt.

“The Dying Slave”, inspired by Michelangelo’s David, was the last work of the artist, who died in 1962. Yves Klein was attracted by the tragic force of this grandiose piece by Michelangelo. By replicating it with his “International Klein Blue” he makes it his own, investing it with a new meaning: turning the slave nightmare into a utopia of liberation.

IKB on canvas, body and space

Yves Klein’s work marked a before and after in the history of contemporary art. His IKB opened up a new way of relating color, body and space, demonstrating that art can be born from the purity of a single hue. In its apparent simplicity, Klein blue contains infinite depth: a reminder that sometimes the most radical gesture is to look at a single color and discover a whole universe in it.

Discover the work of Yves Klein and other great contemporary artists at the upcoming Contemporary Art auction on November 18.

If you liked this article, you may be interested in: