Olivier Bro de Coméres, a romantic painter in the East

The story of Olivier Bro de Comeres seems like the prelude to Lawrence of Arabia or some heroic novel. His biography has gone unnoticed for more than a century, until today.

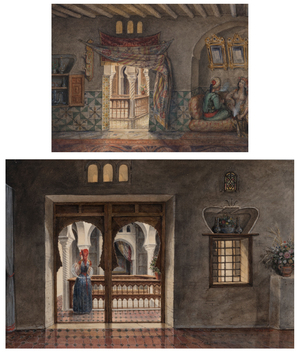

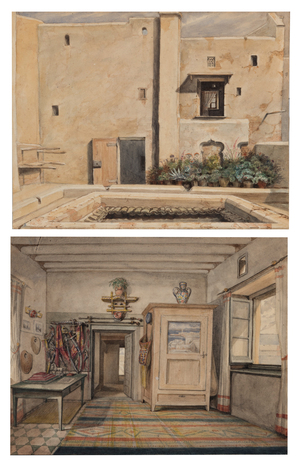

Behind a red leather cover embroidered in the oriental style was hidden one of the best examples of painting and history of romanticism. The drawings it contained could well have passed as simple artistic notes. However, its value goes far beyond that, since, in addition to possessing the air of a novel yet to be written, it becomes an invaluable graphic testimony that treasures multiple architectural, ethnographic, historical and botanical records.

The fascination for the exotic and orientalist world dates back to the Middle Ages, when Venice became a veritable trading empire. However, it was not until 1798 when, after Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt, a real fever was unleashed in Europe for everything related to the Egyptian and Arab world.

This expedition included military men and scholars from different fields: draughtsmen, botanists and architects who fulfilled their task of collecting the notes of each and every one of the wonders of the Egyptian past and its nature. All these works were compiled in the book, “Description de l’Égipte”, published between 1808 and 1822 and whose reading deeply penetrated Olivier’s mind. Once settled in Algeria and feeling like one of those scholars of the Egyptian expedition, Bro de Comeres reflected through his drawings an evident intention to record all aspects of a culture practically unknown to Europeans.

The origins of this story go back to Paris in the early 19th century, when General Louis Bro, one of the leading figures of his time, was sent in 1833 to conquer Algeria. On this mission he was accompanied by the young 21-year-old officer Olivier Bro, who from the moment he arrived in the city of Alger, devoted himself to record in his notebooks different aspects and impressions of the place, from its perspectives and buildings, to its people and customs.

His fascination with drawing a culture that was not his own led him to reproduce the smallest and most anecdotal details very quickly, as is corroborated in the 20 drawings he made in just one month. In them, one can feel the will to bet on veracity, showing, above the aesthetic aspects, the daily life of each scene.

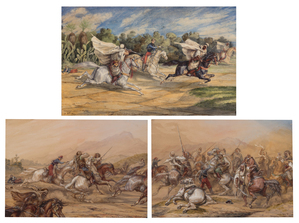

An example of this are these drawings where the artist immerses us fully in the atmosphere of the environment, capturing with total veracity a vivid moment. Proof of his accuracy in representing each of the characters and environments are the notes that he himself wrote on the back of the works in relation to the names, professions and personal details of the life of each one of them.

It is also worth mentioning the prominence of women in his work, regardless of their origin, religion or social position. Among them, the ones known as odalisques stand out, who with their sensual appearance and dressed in luxurious dresses, jewelry and embroidery become one of the most attractive features of the collection. His enigmatic ladies, who appear in scenes of seduction with the artist himself, acquire a real presence that, far from being a prototype, hide their own biographies.

Finally, taking into account his military work in Algeria, we cannot fail to mention the battles, sieges, soldiers and camps whose representation becomes an unparalleled historical document. As if he were a war reporter, Oliver Bro informs us of various events such as the capture of the city of Constantine or the destruction of the city of Medea. Also of great interest are the drawings taken during the battles for the relatives of the fallen or wounded soldiers in which their struggle is heroically described.

The whole ensemble is a valuable piece of history that has remained alive thanks to the dedication and passion of figures such as Olivier Bro de Comeres.